Why meal timing matters (part 1): what is a circadian rhythm and why is it important?

A great deal of research suggests that there are better times to eat – for health, performance and body composition. The science suggests that much of this is related to circadian rhythmicity. Therefore, in this article I will cover a brief overview of circadian rhythmicity, the bidirectional relationship between your circadian rhythm and diet and the broader implications to health.

Keen to go straight to the practical recommendations for when to eat? Click for part 2 here.

Otherwise:

- What is a circadian rhythm?

- How are circadian rhythms regulated?

- Why is your circadian rhythm important?

- What is the interaction between your circadian rhythm and your diet?

- Recommendations

What is a circadian rhythm?

Within biology many processes operate in a cyclical manner with specific rhythms – for example, wake/sleep, feed/fast, light/dark, activity/rest.

For example, a sleep cycles operate within a 90 minute duration (this is an ultradian rhythm since it lasts less than 24 hours) and the menstrual cycle operates within a 28 day period (this is an infradian rhythm since it lasts more than 24 hours).

A rhythm of about 24 hours is what we define as a circadian rhythm – examples of processes that have circadian rhythmicity include:

- Hormones – e.g. insulin, melatonin, cortisol, leptin

- Immune system activity – e.g inflammatory substances such as TNF (tumour necrosis factor)

- Sleep / wake cycle – sleep anticipation in the brain default mode network (DMN)

- Body temperature – reaches peak during middle of day and minimum point at night

Key definitions

Circadian: about a day (Latin ‘circa diem’)

Chronobiology: specific rhythms that occur in biology due to internal biological clocks.

Chrononutrition: the interplay between nutrition and circadian biology.

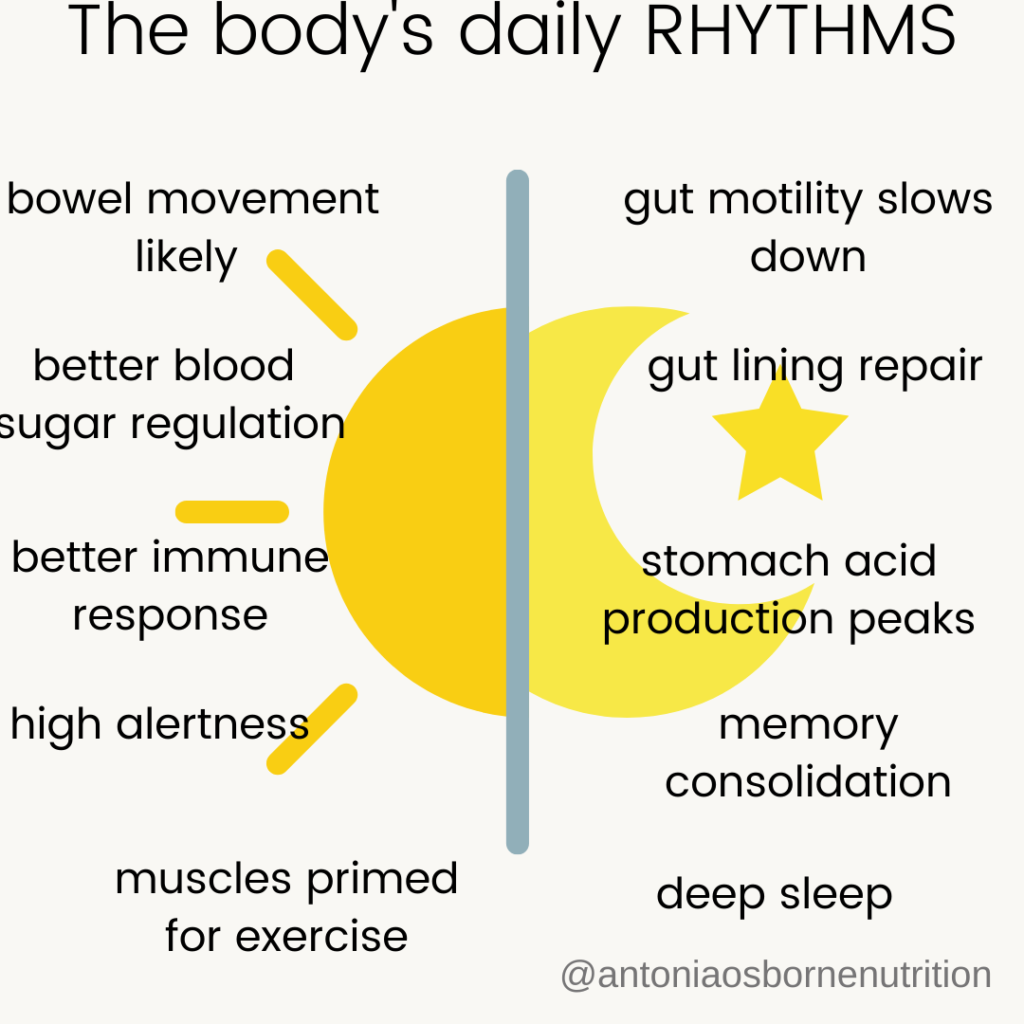

The below image shows how different processes within the body are more or less effective during the the 24 hour period.

How are circadian rhythms regulated?

We have a master clock that regulates circadian rhythmicity throughout the body. It is in a part of the brain called the hypothalamus and is a bunch of neurons (brain cells) we call the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN).

There are also circadian clocks in cells throughout the rest of the body, such as the gut, liver, pancreas, adipose tissue and muscle – called peripheral clocks.

By definition, a circadian clock maintains this approximate 24-hour time period rhythmicity without any external influences. At a celluar level, this is due to the regulation of gene expression which results in particular physiological processes being more or less active within a 24 hours period, or known as having a diurnal pattern (1).

However, it becomes complex because there are certain factors that can influence and set circadian rhythms – in German the word for this is zeitgeber. The most powerful zeitgeber is light!

We have specialised cells with a photo-pigment called melanopsin, in the part of the eye called the retina, that detect light. The master clock, the SCN, is actually attached to the retina and receives light as a signal, enabling it to synchronise the body to the solar day or day/night time.

The SCN projects to other centres within the brain which can then communicate with the local peripheral circadian clocks throughout the body, coordinating them to be in sync with the day-night cycle

Although the peripheral clocks are regulated by the master clock (SCN), they can also regulate their rhythmicity independently and can be influenced by other zeitgebers that the master clock (SCN) cannot by influenced by, such as when we eat and temperature. These peripheral clocks are important for control the timing and rhythmicity of processes such as digestion, nutrient metabolism and appetite.

Why is your circadian rhythm important?

For physical and mental wellbeing, we require alignment between the master clock (SCN) and peripheral clocks. Disrupted circadian rhythms, which occur when there is misalignment, are associated with poor health and increased risk of chronic disease (2).

When someone is in circadian misalignment, it is likely to manifest as the following: poor blood sugar management, disrupted and elevated hunger, increased risk of insulin resistance and an unhealthy stress response. This is then associated with unhealthy lifestyle habits, such as being sedentary, eating too much and poor sleep, which is then associated with increased risk of being very overweight and developing chronic disease such as type 2 diabetes as well as poor mental health like depression (3).

Therefore we need to sync the habits that can influence the regulation of our circadian rhythm, such as viewing daylight, sleeping and eating food, so that there is alignment and our biological processes operate optimally. Then we can feel and function at our best.

What is the interaction between your circadian rhythm and your diet?

The master clock (SCN) directly and indirectly influences the feeding–fasting cycle and habits around food (e.g. hunger, appetite, fullness). When we eat, in turn influences the peripheral clocks that signal back to the brain through nutrients, hormones and how physically full our stomach is to regulate both food intake and/or circadian rhythmicity.

There is a bi-directional relationship between when we eat and circadian biology –

- When we eat impacts circadian rhythmicity: when we eat and the metabolic processes that take place due to eating a meal (digestion, absorption etc) can modify the peripheral clocks. For example, release of the hunger hormone ghrelin is influenced by when we regularly have meals.

- Circadian rhythmicity impacts when we eat: processes related to metabolism, digestion and hormone secretion have circadian rhythmicity. For example, levels of the hunger hormone ghrelin are higher in the evening.

What this means:

When we eat can impact our circadian rhythm: and has the potential to influence our circadian alignment or misalignment – (although not to the same extent as light).

Our circadian rhythms impacts our response to eating a meal: and therefore there may be “better” or “worse” times to eat based on our circadian clocks.

Many processes that impact how food is broken down, digested and absorbed, have a circadian rhythm: – examples include:

- Gastric emptying: the rate of stomach emptying for the same meal is considerably higher in the morning (4). Which may translate into digesting a meal more effectively in the morning than in the evening.

- Beta cell function: insulin sensitivity is on average 15% higher in the morning (4). Which may translate into a better blood sugar response to consuming higher sugar foods (e.g. carbohydrates).

- Post meal blood sugar response: there are greater blood sugar peaks when the same meal is eaten in the evening than in the morning (4). Which may translate into better blood sugar management for consuming more food in the morning.

- Diet induced thermogenesis: may be 44% lower in the evening than in the morning (5). Which may translate into increased calorie burn in the morning versus in the evening – however, I would note that research in this area is still mixed.

- Ghrelin: the hunger hormone, peaks at night and becomes increasingly high when your circadian rhythm is misaligned. This may translate into increased cravings and hunger in the evenings.

- Stomach acid secretion: stomach acid secretion peaks in the evening. (4) This could translate into increased likelihood for acid reflux when eating a larger meal in the evening.

- Gut health: the function and the composition of the bugs in your gut (microbiota) have a diurnal pattern, with cell growth, DNA repair and energy metabolism peaking during the night (4). What this may translate into is night time being the ideal opportunity for your gut bugs to maintain and optimise health.

Whilst the research is mixed, it indicates that the following habits may impact our circadian alignment:

- Skipping breakfast (6,7,8,9)

- Eating late at night (11,12,13)

- Shift work (10)

- Erratic eating patterns (15)

- Eating a large dinner versus a large breakfast (14)

- A prolonged eating window

But, the outcomes from the research are not conclusive and do vary depending upon who is studied, as well as other factors, such as meal composition and the calorie split of meals etc. More research is definitely needed on people who are active, fit and healthy – which will likely be different.

Recommendations

- Consider eating calories in accordance to your activity: whilst eating during daylight and consuming more calories earlier on in the day may be beneficial in some respects since the body is more primed to respond to food, it is also important to consume meals around when you are active – both working and training. The brain and the muscles both require nutrients and energy. For someone who is more active, they will also benefit from a longer window in which they consume food and a small snack before bed may be beneficial for both fat loss and muscle gain. There is also much more research needed on how eating at certain times impacts those who train since most of the research has been carried out on people who are overweight and diabetic and therefore it is not necessarily translatable.

- Consider creating a routine that suits your needs & lifestyles: having a routine that you can be consistent with and helps you to be healthy most of the time and then adapt when need be so it should not become a stress. Create this routine around your day and what works best for you.

- Note eating in line with your circadian rhythm may not be the same as nutrient timing: meaning how you fuel your body to optimise your training and recovery – which has very different implications. I have written an article here on nutrient timing.

Related articles

Why meal timing matters (part 2): what time is best to eat?

Nutrient timing – what’s the deal and does it matter when you eat?

References

- Partch et al. (2014). Molecular architecture of the mammalian circadian clock.

- Panda (2016). Circadian physiology of metabolism.

- Scheer et al. (2009). Adverse metabolic and cardiovascular consequences of circadian misalignment.

- Segers & Depoortere (2021). Circadian clocks in the digestive system.

- Morris et al. (2015). The human circadian system has a dominating role in causing the morning/evening difference in early diet-induced thermogenesis.

- Ogata et al. (2019). Effect of skipping breakfast for 6 days on energy metabolism and diurnal rhythm of blood glucose in young healthy Japanese males.

- Thomas et al. (2015). Usual breakfast eating habits affect response to breakfast skipping in overweight women.

- Betts et al. (2014). The causal role of breakfast in energy balance and health: a randomised controlled trial in lean adults.

- Chowdhury et al. (2016). The causal role of breakfast in energy balance and health: a randomised controlled trial in obese adults.

- Qian et al. (2018). Circadian misalignment increases the desire for food intake in chronic shift workers.

- Naimi et al. (2004). Postprandial metabolic profiles following meals and snacks eaten during simulated night and day shift work.

- Qian et al. (2019). Ghrelin is impacted by the endogenous circadian system and by circadian misalignment in humans.

- Qian et al. (2018). Differential effects of the circadian system and circadian misalignment on insulin sensitivity and insulin secretion in humans.

- Jakubowicz et al. (2013). High calorie intake at breakfast vs dinner differentially influences weight loss of overweight and obese women

- Gill & Panda (2015). A smartphone app reveals erratic diurnal eating patterns in humans that can be modulated for health benefits.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Subscribe to my monthly newsletter

Site Credit

LEGAL

FAQS

CONTACT

© 2023 Antonia Osborne

Antonia,

MSc, RNutr

Performance Coach

Registered Sports & Exercise Nutritionist